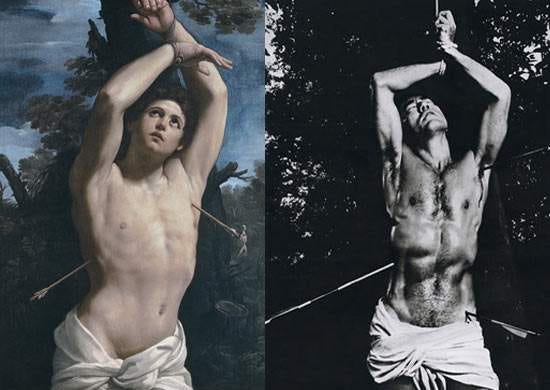

Below is a sample of my latest work, Gods and Monsters.

Art can be an intoxicating thing, with the power to transform lives in unexpected and auspicious ways. When the great Japanese writer, Yukio Mishima, as a 12 year old schoolboy, stumbled upon a painting of Saint Sebastian in one of his father’s art books, the budding writer had a spiritual and sexual awakening that would influence his writing for the rest of his life. Consider this excerpt from Yukio Mishima’s 1948 apparently autobiographical novel, Confessions of a Mask.

One day, taking advantage of a slight cold that had prevented me from going to school, I fished out some volumes of reproductions of works of art that my father had brought back home as souvenirs of his travels in foreign lands, and taking refuge in the bedroom I examined them with great attention. I was especially fascinated by the photogravures of Greek sculptures in the guidebooks of various Italian museums. When I found myself before the representations of the nude, among the many reproductions of masterpieces, it was these black and white plates that satisfied my imagination in preference to any other. This was probably due to the simple fact that, even reproduced, sculpture seemed to me closer to life.

It was the first time I had seen books of that sort. My miserly father, intolerant of the idea that childish hands had to touch and sully those figures, and fearing moreover - how wrongly! - that I might be attracted to the naked women in the masterpieces, had stowed the volumes away in the deepest recesses of a cupboard. As for me, I had never dreamed until that day that they could be more interesting than the cartoons in the boys’ magazines.

I was flipping through one of the last pages of a volume. All of a sudden, from the corner of the next page, there flashed before my eyes an image that I had to assume had lurked there for my benefit alone.

It was a reproduction of Guido Reni’s Saint Sebastian, which figures in the collection of Palazzo Rosso in Genoa.

The trunk of the tree of torment, black and slightly oblique, stood out against the Titianesque background of a gloomy forest and a serene sky, gloomy and distant. A young man of singular loveliness stood bound naked to the trunk of the tree, his arms drawn up, and the straps that clasped his crossed wrists were fastened to the tree itself. No ties of any other kind were discernible, and the only covering of the young man’s nakedness consisted of a rough white cloth that loosely wrapped around his loins.

I imagined that it was a description of a Christian martyrdom. But since it was due to a painter of the eclectic school derived from the Renaissance, even from this painting depicting the death of a Christian saint exuded a strong aroma of paganism. The young man’s body - one could even compare it to that of Antinous, Hadrian’s favorite, whose beauty was so often immortalized in sculpture - bears no trace of the hardships or exhaustion derived from missionary life, which imprint the effigy of other saints: instead, this one uniquely manifests the springtime of youth, uniquely light and pleasure and gracefulness.

That white and incomparable nudity of his sparkles against a background of twilight. His sinewy arms, the arms of a praetorian accustomed to flex his bow and brandish his sword, are raised in a harmonious curve, and his wrists cross immediately above his head. The face is turned slightly upward and the eyes are wide open, contemplating the glory of heaven with deep tranquility. It is not suffering that hovers over the expanded chest, the taut abdomen, the barely twisted lips, but a flicker of melancholy pleasure like music. Were it not for the arrows with their points stuck in his left armpit and right hip, he would rather look like a Roman athlete relieving fatigue in a garden, leaning against a dark tree.

Arrows have plunged into the heart of the young, pulpy, fragrant flesh, and are about to consume the body from within with flames of heartbreak and supreme ecstasy. But the blood is not gushing out; the swarm of arrows seen in other paintings of St. Sebastian’s martyrdom has not yet raged. Here instead, two lone arrows send their quiet and delicate shadows over the smoothness of the skin, similar to the shadows of a branch falling on a marble staircase.

But all these interpretations and discoveries came later.

That day, the moment I glimpsed the painting, my whole being quivered with pagan joy. My blood roiled in my veins, my loins swelled almost in an emptiness of rage. The monstrous part of me that was close to exploding waited for me to use it with unprecedented ardor, rebuking my ignorance, gasping in outrage. My hands, not at all unconsciously, began a movement I had never learned. I felt something secret, something radiant, launching itself rattily to the assault from within. It erupted suddenly, bringing with it a blinding intoxication....

Some time elapsed and then, in a desolate mood, I looked around at the desk I stood in front of. Outside the window a maple tree was casting a vivid glare everywhere -- on the ink bottle, on school books and notebooks, on the dictionary, on the image of St. Sebastian. Splashes of a dim whiteness appeared here and there - on the title in gold letters of a textbook, on the margin of the inkwell, on an edge of the dictionary. Some objects dripped lazily, others glowed with a dim gleam like the eyes of a dead fish. Fortunately, a reflexive movement of my hand to protect the figure had prevented the volume from soiling.

That was my first ejaculation. And it was also the clumsy and totally unplanned beginning of my “bad habit.”

Guido Reni, also known as “the Divine Guido, (4 November 1575 – 18 August 1642) was an Italian painter, fresco artist and etcher, active during the Baroque period. He painted primarily religious works, but also mythological and allegorical themes. Active in Rome, Naples, and his native Bologna, he became the dominant figure in the Bolognese School that emerged under the influence of the Carracci family which consisted of brothers Annibale and Agostino and cousin Ludovico. After a fall out with Ludovico over unpaid work, Guido followed Annibale to Rome in 1601 to paint frescoes in the Palazzo Farnese. By 1604, the talented Guido was receiving independent commissions and became one of the premier painters during the papacy of Pope Paul V and between 1607 and 1614, he was a favored painter, patronized by the Borghese family.

Guido returned to Bologna in 1615, and created one of his most reproduced and famous works, Saint Sebastian, referred to by Italians as San Sebastiano. The painting is thought to have been commissioned by a member of the papal court, due to the presence of lapis lazuli in the blue of the sky, an expensive material usually supplied by wealthy clients. Guido was a bit obsessed with Saint Sebastian, painting him a total of six times. The reproduction of Sebatian that Yukio Massima encountered is arguably the most recognizable. The painting doesn’t depict a martyr scarred by arrows and wounds dripping with blood, rather Guido serves us an idealized body of a young man with a decidedly sensual beauty. Sebastian looks heavenly, not in pain, but in ecstasy. It is obvious why Oscar Wilde and other gay artists experienced similar encounters with the potent and powerful work.

Guido Reni’s painting of Saint Sebastian is preserved at the Musei di Strada Nuova Palazzo Rosso.